This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Badeschiff. Floating Swimming Pool in Berlin

Technical Data:

Architects: Fernando Menis, Felipe Artengo Rufino, José María Rguez. Pastrana with Gil Wilk.

Artist: Susanne Lorenz.

Location: Berlin. Germany. 52°29’52.6″N 13°27’13.4″E

Budget: 400.000 Euros.

Building surface: 240 m2

Status: Built 2004.

Client: Stadkuntprojeckte e.V. Berlin, Heike Catherina Müller.

Company: Ute Schimmelpfennig für m.o.l.i.t.o.r. GmbH, Berlin.

Contractor: MBS-Márkische Bunker und Service GMBH & KG, Berlin.

Awards: Competition, 1st prize Finalist in the Spanish Architecture Awards VIII Biennial of Spanish Architecture Finalist in the IV Urban Public Space European Award Selected for the Venice Architecture Biennale

Description: Following Berlin’s public pools tradition in the Spree at the end of the 19th century, this project brings back to the city a closer relation with the river, by embedding a floating pool. The pool is located in the centre of Berlin, inside the river, in an old barge of coal, alike the ones that still transport daily materials on the river. The barge was reconverted into a pool and a wood platform was added to, taking the role of a beach that allows it to be a leisure space where to relax and enjoy.

Since the time of the ancient Rome, the pools and thermal baths have been a meeting point for enjoying both nature and water; the Spreebrücke– as it’s known in German-, is a clear example of it. The project takes as much literally as figuratively the concept of a bridge: It is seen not only as a connexion between two points, but also as a connecting line, with meeting points, inside the city.

Formerly, the Spree River performed an important role in the social life in Berlin. Just like in other European capitals, during the 18th and 19th centuries, the construction of bridges downtown became a very profitable activity that created models highly loaded on symbolism and representability. During the Second World War, with the exception of Weidendammer and Schilling’s bridges, all bridges in Berlin were totally or partially destroyed by bombs. The limits between East and West Berlin were not only drawn by the historical wall, but also by the suppression of the bridges that used to cross the river and so connect its two sides.

The bridges constructed after the war were austere engineering works, which avoided every functional drift, limiting themselves to give a practical and efficient response to the communication needs that emerged during the process of reconstruction of Germany. Shortly after, the divided city would turn its back to the river, which coincided majorly with the border between the two sides. Even more, the presence of the Spree came to be perceived as a continuation of the wall that has been dividing Berlin for so many years.

On the other hand, at the beginning of the 20th century, there were fifteen common public bathrooms on the borders of the Spree. Some were delimited places in some parts along the river and others were near raft known as Badeschiffe (bath-boats) that supplied on the river’s waters. However, the crescent pollution of the river’s waters provoked the closing of public bathrooms before the First War World.

Since the German unification in 1989, the government has made large investments on the restoration and construction of new bridges and connexions. In this send Spreebrücke Berlin is a project, which took the challenge of uniting the city again. Fernando Menis’s team adopted the idea of the reunification taking advantage, not only of the existence of the Spree, but also, of its intensive historical and industrial uses. It is precisely the previous industrial use of the river that is an inspiration for this new intervention, as well as the Berliners’ habit of going to the river at the beginnings of the century as previously mentioned.

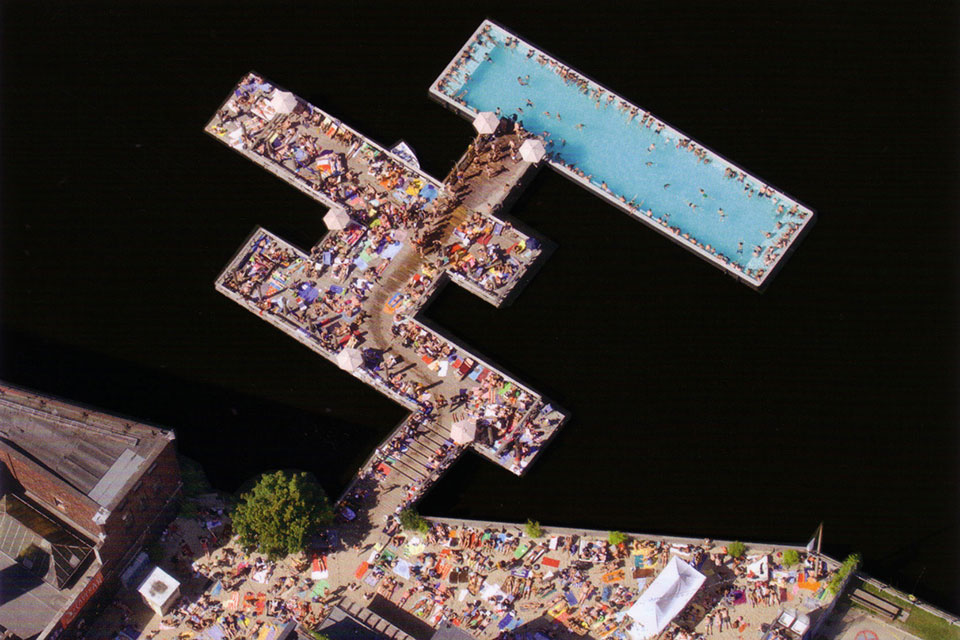

The project was promoted, as much architectonically as artistically, by the Stadtkunstprojekte e.V. under Heike C. Muller’s curatorship. In 2012, the German State Association Stadtkunstprojekte (Cultural Project in the City) organized an international call for integrating the Spree River in the city. It was actualy a multiple competition that, under the name of “con_con” [destroyed connexions], gathered artists, architects and engineers to develop a series of intervention that would look forward the reestablishment of the bridges and edges of the Spree as vital spaces of the city. The Canarian architecture studio and the Berliner artist, Susanne Lorenz, won the contest in which thirty-two contestants from twelve countries had participated. The result, a highly innovative facility completed in 2004, is having a great positive impact on Berlin’s social life and economy. It is a place of leisure which works as a tool for optimizing and activating this part of the city, located in the highly transited neighbourhood of Treptow, in Kreuzberg.

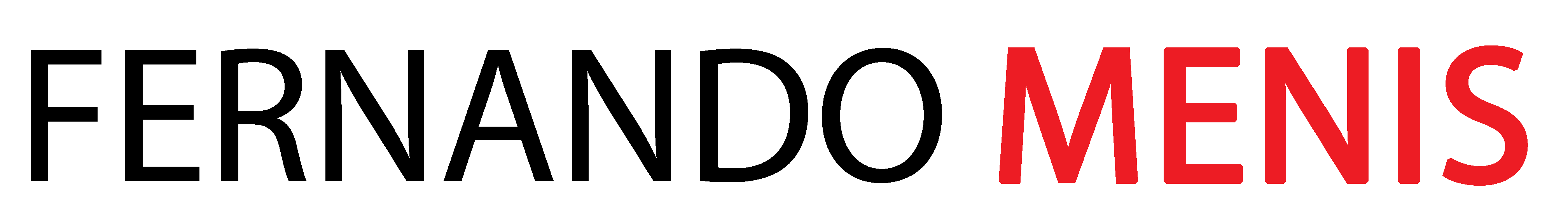

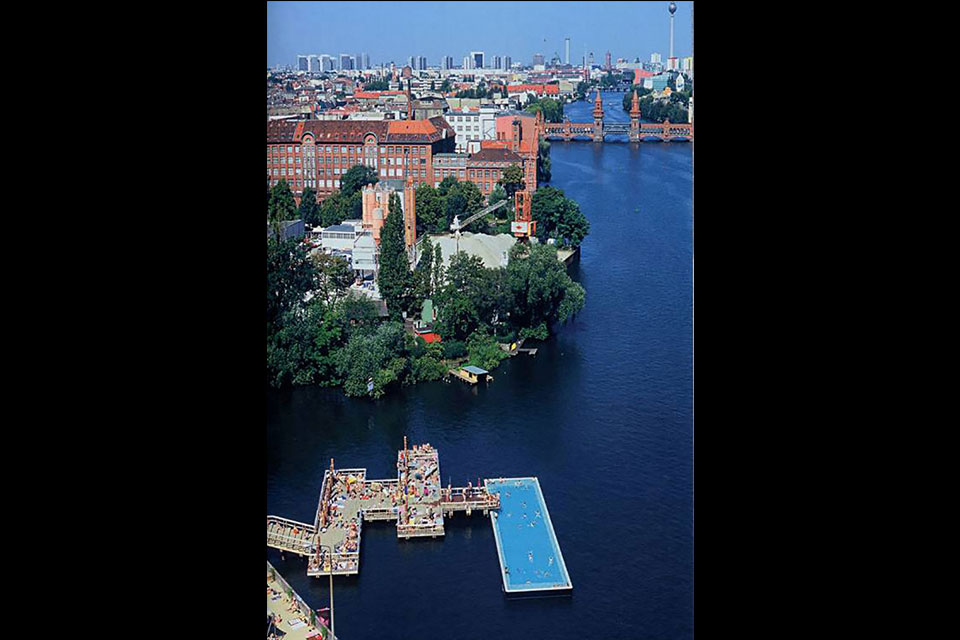

The project consisted on recycling a sunken boat, into a public floating pool, proposing a new recreation space next to the former wall of Berlin. The product is a pool with Caribbean blue crystaline water, submerged and contrasting with the Spree’s dark water. The wooden bridge is the access to the pool from a fictitious beach. Visually, it looks as if the visitors took a bath in the river, while actually they immerse into an old industrial barge, a cargo boat that used to transport coal and now recycled, drowned in the waters of a river that is searching to take an active part in the city.

The Spreebrücke is, therefore, a new floating bath zone that can be disassembled and transported at any other point of the river. It is currently installed on the South-East of the city, just before the Oberbaumbrücke’ bridge. It counts a pool, an artificial beach, a bridge and a container. Originally, the idea was to make a round pool. The team, next to Frei Otto – who was on vacation on Tenerife at the time of designing – tried to formalize this idea, and finally, searching for a low cost proposal, chose the very interesting idea to transform and recycle a Schubleichter, a type of barge very commonly used for the transport in the Spree. After retiring the cover of the boat, the helmet formed a floating rectangular recipient that draws itself on the surface of the river by a rectangular clean water area for swimming in summer and ice-skating in winter. Electric blue and green lights recessed in the interior walls of the recipient illuminate the surface of the water with the summery colours from the Caribbean or Canarian islands, longed by the Berliners, as a blue line, gleaming and permeable: Water flying over water. Depending of the flow of the Spree, the pool floats or rests on the riverbed, so its surface can stay lower or higher than the river level.

Approaching to the river, in the sand appears a walkway towards two big wooden platforms that takes the role of artificial beaches where to sunbathe and rest next to the pool. These connect with the old cargo barge turned into a “bath-boat”. The flatboat, an old recycled Schubleichter the size of which is optimal for swimming because of its dimensions: 5 meters long, 8, 2 meters width and a bit more than 2 meters depth. It contains 400.000 litres of water lightly chlorinated kept at 24 °C. The engineer of the group, Juan José Gallardo, calculated the load of the liquid and the weight of the barge itself, so that when totally filled, it would stay 70 centimetres higher than the river surface. The idea was to match the level of the water with the edges of the pool so the swimmers would feel totally immersed in the mass of the river. For this purpose and using the curves of the draught, it was added to the air chamber, contained in the double framework of the cargo vessel, a base of expanded polystyrene that reduces the weight and obtains the required shift.

This pool represents the universal archetype of ideal public space by its capacity to interweave architecture and city without establishing any frontier between them. On the other hand, the adaptive reuse of the Schubleichter that constitutes the recipient of the pool, is a reference to a local dimension of the project that englobes the wealthy tradition of nautical industry of the Spree River.

With the proposal of the contemporary “bath-boat”, the design team wanted to recover the practice of baths and associate this activity to the beach bars too. The new “Spree bridge” connects with the past, with a lost tradition, and with the present as a place of communication. This concept and design fascinated AREBA, a German private company, which built and maintained the pool, as an element of great attractive power.

The collaboration of different professionals turned a lost tradition into a poetic experience and Berlin won a completely new perspective of the city. Since its inauguration twelve years ago, the project has been growing into an example of open-air activities in the South-East part of the centre, a positive change engine and a meeting point for this plural-ethnic neighbourhood of Berlin.

Español

Español